Laundry starch: from medieval luxury to Victorian mass market

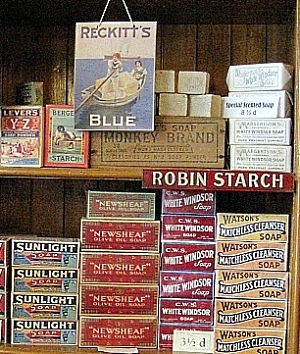

Starch has come a long way: from a sour mix boiled and brewed to a press-button spray. Manufactured starch that could be conveniently mixed at home as "cold starch" without boiling was available by the 19th century, suitable for clothes that didn't need a perfectly clear starch mixture. Victorian science and new styles of commerce made starch into a branded product. Buying it neatly packaged instead of in lumps was not just convenient; it suggested a "modern", well-prepared formula. No wonder one company made its selling point, from about 1881, the cardboard box its starch was sold in. (See advertising photo right)

Starch has come a long way: from a sour mix boiled and brewed to a press-button spray. Manufactured starch that could be conveniently mixed at home as "cold starch" without boiling was available by the 19th century, suitable for clothes that didn't need a perfectly clear starch mixture. Victorian science and new styles of commerce made starch into a branded product. Buying it neatly packaged instead of in lumps was not just convenient; it suggested a "modern", well-prepared formula. No wonder one company made its selling point, from about 1881, the cardboard box its starch was sold in. (See advertising photo right)

It's often said that starching was "introduced" in the 16th century when it was essential for fineruffs and fluted collars, but that's not accurate. Starch was already in use for fine linens and laces, but in the 1500s starchmaking became more organised and commercial in Northern Europe. Flanders, home of the famous Flemish lace, was one of the earliest centres of starch manufacturing and skilful use. A Dutchwoman brought some of that knowledge to Elizabethan London, and set herself up as an expert at a time when there was high demand for well laundered and elaborate collars and cuffs. And that's why some websites tell us that starch "arrived" in 1564.

Early use of starch

Laundry was not a hot topic for medieval writers and there's not a lot known about it before the age of ruffs. The first clues in English are from the 14th century.* Then 'starch for kerchiefs' appeared in a 1440 dictionary.* Also around 1440, we know the nuns of Syon Abbey were starching altar cloths and other church linens. Only starch "made of herbes" could be used for communion linen.* This was probably prepared from the roots of the cuckoo-pint flower (arum maculatum or starchwort):

Laundry was not a hot topic for medieval writers and there's not a lot known about it before the age of ruffs. The first clues in English are from the 14th century.* Then 'starch for kerchiefs' appeared in a 1440 dictionary.* Also around 1440, we know the nuns of Syon Abbey were starching altar cloths and other church linens. Only starch "made of herbes" could be used for communion linen.* This was probably prepared from the roots of the cuckoo-pint flower (arum maculatum or starchwort):The most pure and white starch is made of the rootes of the Cuckoo-pint, but most hurtful for the hands of the laundresse that have the handling of it, for it chappeth, blistereth, and maketh the hands rough and rugged and withall smarting.

Gerard's Herbal, 1633

Ordinary starch was made by boiling bran in water, then letting it stand for three days, according to a 15th century recipe.* Once the bran had been strained out, cloth was dipped in the sour, starchy water, dried, then smoothed and polished with a slickstone. For obvious reasons starch was a bit of a luxury. Who had time for all that? Although professional 'starchers' existed before elaborate ruffs came into fashion*, from that time on there were more starchmakers, and more laundresses who could handle fine lawn and cambric trimmings.

Coloured starch

The 17th century saw a controversial fashion for ruffs laundered with "yellow starch", and then red or green starch. In London this provoked disapproval, mockery, and was linked with scandal. (See Renaissance Clothing

The 17th century saw a controversial fashion for ruffs laundered with "yellow starch", and then red or green starch. In London this provoked disapproval, mockery, and was linked with scandal. (See Renaissance Clothing

Tinted starch came back in Victorian times. Packeted écru and buff sold well for use on blonde lace and beige/cream colours, while blue starch continued popular for brightening whites. More unusual colours were marketed but didn't sell as well.

JUST LANDED: Reckitt's COLOURED STARCH, Pink, Ecru, Heliotrope, in boxes 6d. each, far superior to any other brands.

The Mercury, Hobart, Tasmania, 1896

Gloss, glaze, and gleam

Recipes and household tips from the past remind us that most fabrics looked limp and crumpled after laundering. There were special instructions for starching delicate, droopy muslins. Starch helped make clothes and table linen firmer and glossier, and you could add extra ingredients for an even better finish. A little candle grease or cooking fat went into starch mixtures for more gloss. Salt was the most common ingredient recommended for helping the ironing to go smoothly.

Recipes and household tips from the past remind us that most fabrics looked limp and crumpled after laundering. There were special instructions for starching delicate, droopy muslins. Starch helped make clothes and table linen firmer and glossier, and you could add extra ingredients for an even better finish. A little candle grease or cooking fat went into starch mixtures for more gloss. Salt was the most common ingredient recommended for helping the ironing to go smoothly.There are various things which diferent people mix with their starch, such as alum, gum arabic, and tallow, but if you do put anything in, let it be a little isinglass, for that is by far the best. About an ounce to a quarter of a pound of starch will be sufficient.

The complete servant maid: or young woman's best companion. Containing full, plain, and easy directions..., Anne Barker, c1770

All the well-known recipes were imitated by 19th and 20th century manufacturers who emphasised gloss in their advertising and chose brand names like Fairy Glaze. Borax was often added to increase gloss. Not sticking to the iron and ease of mixing were other key qualities. Added bluing was a desirable extra for use on white laundry. However much soaking, boiling, scrubbing and bleaching you did, blue would make whites gleam more brightly.

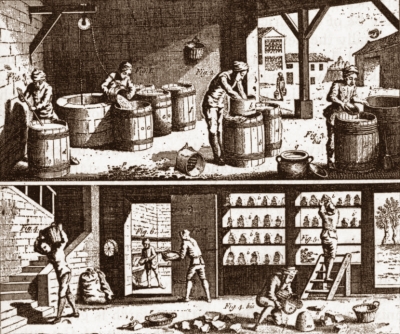

All the well-known recipes were imitated by 19th and 20th century manufacturers who emphasised gloss in their advertising and chose brand names like Fairy Glaze. Borax was often added to increase gloss. Not sticking to the iron and ease of mixing were other key qualities. Added bluing was a desirable extra for use on white laundry. However much soaking, boiling, scrubbing and bleaching you did, blue would make whites gleam more brightly. Starchmaking could take up to a month, with long boiling, soaking, draining, rinsing, drying and so on. In the 17th century the use of wheat was criticised as wasting food on fashion. The 18th century saw experimentation with different sources of starch, including horse chestnuts and potatoes. In the 19th century new ingredients and manufacturing methods were developed in the quest for pure white, refined starch. Rice starch was considered to give a good glazed finish. Corn starch made a more opaque mixture but could be made at home. There were recipes for this and other starches in US domestic advice manuals. It was also used in North American branded laundry starch products: often called "gloss starch" to distinguish it from cooking starch.

Starchmaking could take up to a month, with long boiling, soaking, draining, rinsing, drying and so on. In the 17th century the use of wheat was criticised as wasting food on fashion. The 18th century saw experimentation with different sources of starch, including horse chestnuts and potatoes. In the 19th century new ingredients and manufacturing methods were developed in the quest for pure white, refined starch. Rice starch was considered to give a good glazed finish. Corn starch made a more opaque mixture but could be made at home. There were recipes for this and other starches in US domestic advice manuals. It was also used in North American branded laundry starch products: often called "gloss starch" to distinguish it from cooking starch.

Even when some starch could be used "cold", home boiling with water and other additives continued. It depended not only on the type of starch but on the kind of fabric, the judgment of the launderer etc. etc. Some starch mixes were milky and more suitable for thicker fabrics. Good laundresses were expected to "clear-starch": preparing transparent starch mixtures and knowing how to use them. Clear-starching meant keeping delicate muslin and similar fabrics from being clogged with starch granules in the loose weave, and avoiding thickening caused by visible traces of starch clinging to the threads.

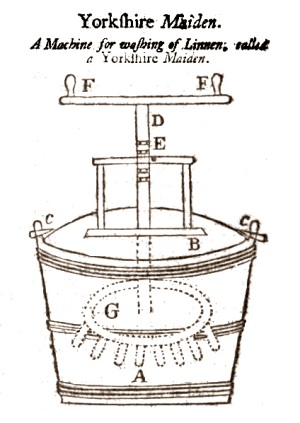

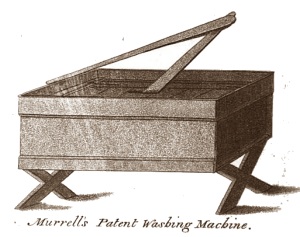

This is not just a story of inventions, inventors and their patents. Patents don't tell us enough about the earliest washing machines. We want to know what machines were actually manufactured. Who sold them? Who bought them? Did people like them?

This is not just a story of inventions, inventors and their patents. Patents don't tell us enough about the earliest washing machines. We want to know what machines were actually manufactured. Who sold them? Who bought them? Did people like them? The idea of washing by machine goes back a long way, but nothing practical happened until the mid-1700s. Before that, three early designs take turns being put forward as "first washing machine ever". An early 17th century book by

The idea of washing by machine goes back a long way, but nothing practical happened until the mid-1700s. Before that, three early designs take turns being put forward as "first washing machine ever". An early 17th century book by  In Germany

In Germany  In 1787 an energetic washing machine publicist came on the scene.

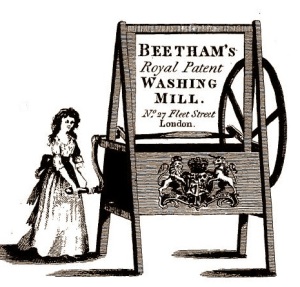

In 1787 an energetic washing machine publicist came on the scene.  This washing machine certainly got attention, but it is hard to know how many homes or institutions used one regularly. Beetham put a series of enthusiastic washing machine ads in newspapers and on fliers. He said he had sold 1121 washing mills in the year from May 1790 to 1791. Apparently 300 people liked them so much they came back for another "in consequence of their entire approbration of the first, and for their different houses". In 1792 he persuaded a

This washing machine certainly got attention, but it is hard to know how many homes or institutions used one regularly. Beetham put a series of enthusiastic washing machine ads in newspapers and on fliers. He said he had sold 1121 washing mills in the year from May 1790 to 1791. Apparently 300 people liked them so much they came back for another "in consequence of their entire approbration of the first, and for their different houses". In 1792 he persuaded a Cutting the costs of paid labour was a big selling point, and it was not only adult washerwomen whose lives could be affected by this. The machines were considered easy enough for a child to operate. Coates and Hancock said a girl of 12 could work two of their machines more easily than a man could work one of any other sort. In fact, a 7-year old could manage the job, they said. A girl would not have earned more than a few pennies for a day's help.

Cutting the costs of paid labour was a big selling point, and it was not only adult washerwomen whose lives could be affected by this. The machines were considered easy enough for a child to operate. Coates and Hancock said a girl of 12 could work two of their machines more easily than a man could work one of any other sort. In fact, a 7-year old could manage the job, they said. A girl would not have earned more than a few pennies for a day's help.

There were huge changes in domestic life between 1800 and 1900. Soap,

There were huge changes in domestic life between 1800 and 1900. Soap,

Other changes in the course of the century included factory-made metal tubs starting to replace wooden ones. Mass-produced tongs were more affordable and more likely to replace sticks for lifting wet washing. Clotheslines, pegs, and pins became more widespread. Home-made clothes pegs and

Other changes in the course of the century included factory-made metal tubs starting to replace wooden ones. Mass-produced tongs were more affordable and more likely to replace sticks for lifting wet washing. Clotheslines, pegs, and pins became more widespread. Home-made clothes pegs and

There were laundry services aimed at the "middling" people too. While the upper classes went on employing

There were laundry services aimed at the "middling" people too. While the upper classes went on employing Once upon a time a metal washboard and bar of hard soap with a tub of hot water was a new-fangled way of tackling laundry, though today it's a common picture of "old-fashioned" laundering. (Read about this on a page about the later

Once upon a time a metal washboard and bar of hard soap with a tub of hot water was a new-fangled way of tackling laundry, though today it's a common picture of "old-fashioned" laundering. (Read about this on a page about the later  Washing clothes in the river is still the normal way of doing laundry in many less-developed parts of the world. Even in prosperous parts of the world

Washing clothes in the river is still the normal way of doing laundry in many less-developed parts of the world. Even in prosperous parts of the world  Domestic laundry was often treated like newly woven textiles being "finished". Today we have only vague ideas about how the fabrics in our shop-bought clothes are manufactured, but traditional laundry methods often followed techniques used by weavers, including home weavers.

Domestic laundry was often treated like newly woven textiles being "finished". Today we have only vague ideas about how the fabrics in our shop-bought clothes are manufactured, but traditional laundry methods often followed techniques used by weavers, including home weavers.

The

The  People also

People also